Bruce Conner

Light Out of Darkness

October 8, 2022–March 5, 2023

Antoni Tàpies

The Fertilizer that Feeds the Soil

Tàpies (1958–88)

October 8, 2022–April 30, 2023

Bruce Conner: Light Out of Darkness

Curator: Roland Wetzel

Bruce Conner, who was born in McPherson, Kansas in 1933 and passed away in San Francisco in 2008, is renowned for both his criticism of the art world and his status as the inventor of the video clip. He has even been referred to as a “artist’s artist,” making him one of the most notable artists of the second half of the 20th century. His political and subversive art is expressed through a variety of media, making him a transversal artist who works in photography, film, collage, drawing, painting, and assembly.

Many of his early collages, assemblages, and installations are comprised of flimsy, transient materials like nylon, wax, or used textiles and are therefore too delicate to be displayed except under extremely unusual circumstances. Conner’s anarchist approach was characterized by his corrosive cynicism, unrelenting commitment, and intent on avoiding the art market at all costs.

Nine pieces, which serve as a good representation of Conner’s experimental film output, are on display. One of these is Crossroads (1976), a movie that compiles images from the first American underwater nuclear testing at Bikini Atoll in 1946 into a 36-minute exploration of the horror and beauty of this cataclysmic event.

The phrase “Light out of Darkness” alludes to a solo exhibition of the same name that was held at Berkeley’s University Art Museum in the 1980s. Conner’s resistance to make concessions in his dealings with institutions, whose standards for artists he would not accept, was one of the main reasons it never happened. The phrase “Light out of Darkness” highlights the experimental nature of Conner’s filmmaking, particularly in his early works, which resemble a masterful exploration of human perceptive potential. The artist’s tendency to think in opposites and analogies as well as his mysticism are symbolized by the dualism of light and darkness in his works.

This exhibition has been realized in cooperation with Museum Tinguely, Basel.

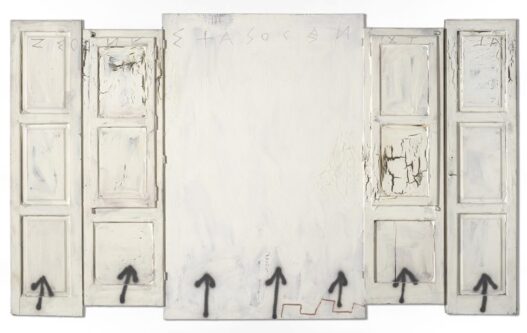

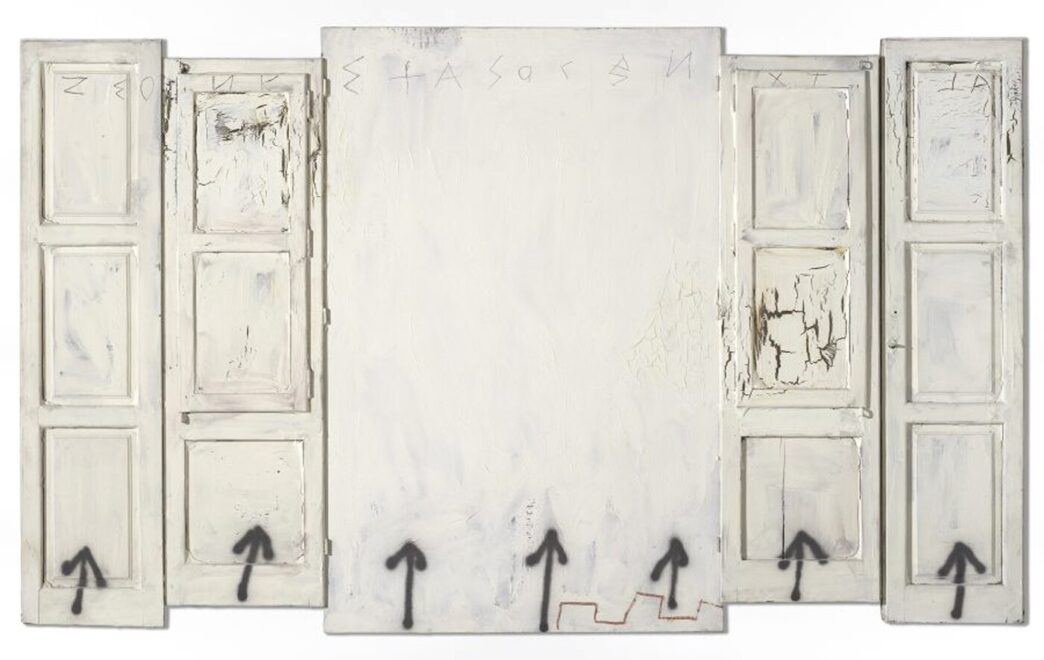

Antoni Tàpies: The Fertilizer that Feeds the Soil. Tàpies (1958–88)

Curator: Núria Homs

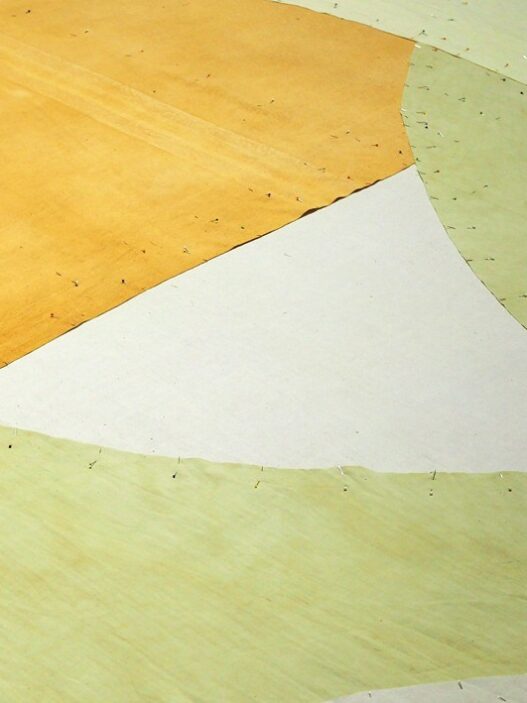

The late 1950s to the late 1980s are the time period covered by this exhibition, which demonstrates the artist’s progression and the links he made between his matter paintings, objects, and varnishes. The revaluation of primary matter, of the natural and ordinary, of all those things that society rejects or hides out of shame, but that for Tàpies are not only endowed with spirituality, but are above all where the origin and the force of life lies, the fertiliser that feeds the soil, is consistent throughout all these works, despite the stark contrast between the opacity of the walls and the humbleness of the objects with the luminosity of the varnishes.

By 1958, both the American and European publics were interested in Tàpies’ work. With the so-called matter paintings, pieces with opaque surfaces that resemble walls, he made his debut in the international art world and signaled the start of his mature phase. These pieces perfectly capture the spirit of his era. They are reminiscent of phenomena that were prevalent at the time, such as the effects of the atomic bomb and new scientific discoveries, the fascination with children’s art and the work of mentally ill people, the fascination with the art of so-called primitive peoples, from prehistory to the present, and the attention to the most neglected and subpar aspects of immediate reality, such as graffiti and abandoned objects as well as the rundown, outlying neighborhoods that remained outside the rationalizing.

Abstract and Informalist have both been used to describe Tàpies’ work frequently. These qualifications, however, are not totally accurate because by the time Marcel Duchamp’s art matured, in the late 1950s, both Informalism and Abstract Expressionism were starting to give way to a new generation of artists who wanted to enlarge the definition of realism. Tàpies shared these worries and, as a continuation of the primitive style of the matter paintings, “towards everything non-industrial, non-designed, or rationalized,” exponentially intensified his work with objects in the 1960s.

Beginning in the late 1970s, more light pieces were added to those that already contained matter and objects, and varnish—a traditional medium in Tàpies’ creative work—became more discernible next to the matter and objects. Varnish, which is a fundamental component of the matter paintings and which Tàpies had previously used as a foundation for marble dust, sand, paints, and other materials, now occupies a central role and offers a transparency that contrasts sharply with the opacity of the walls. He keeps using varnish to depict bodily functions or portions of the body that are deemed unsightly and uncomfortable.

All of Tàpies’ work clearly has a spiritual component. He begins the journey towards enlightenment by appreciating the most basic things, such as straw, dust, a wooden drawer, and the least appealing body parts. This is known as the purgative path, which examines what is most perverse in both the individual and society. His use of disagreeable components aims to stir the viewer’s spirit and arouse consciousness so that art might become a fertiliser for information and a critical spirit.

Fundació Antoni Tàpies

Carrer Aragó, 255

08007 Barcelona Catalonia

Spain

Hours: Tuesday–Saturday 10am–7pm,

Sunday 10am–3pm

T +34 934 87 03 15

museu@ftapies.com