June 10–September 25, 2022

FILMZ evening of anticipation: August 24, 6pm

Artist talk, “Making the unvisible visible”: September 14, 7pm, with Oliver Ressler and Stefanie Böttcher, Director, Kunsthalle Mainz

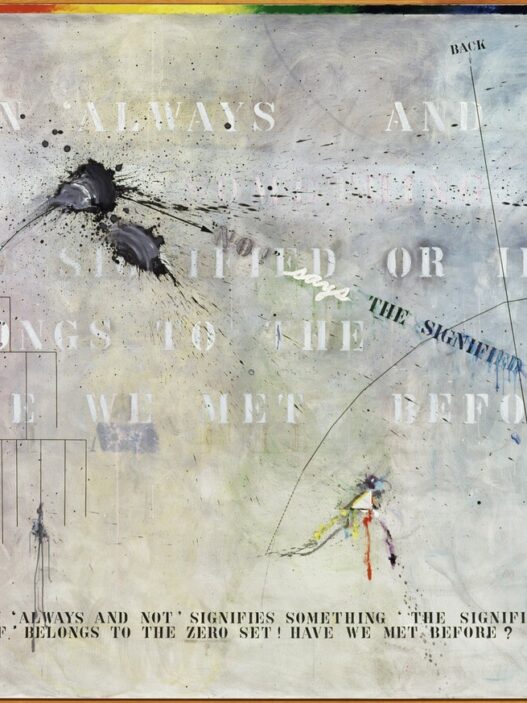

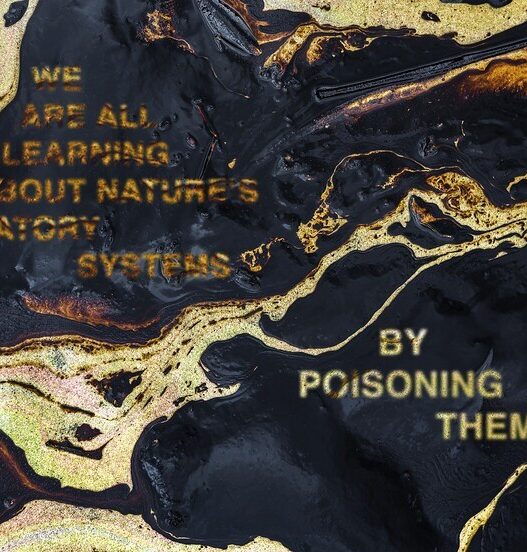

The homosphere, which is essentially our airspace, is where humans function. The atmosphere’s composition is rather consistent in this region, which is the part of the atmosphere that is closest to the planet. It spreads to the edge of space and encompasses the entire planet. There are no curves in space. Unseen gases and elements that are invisible to the naked eye make up this zone, which is delineated by limits that are present but latent. We don’t fully comprehend how much airspace impacts us as individuals compared to how much it influences the ground on which we walk unless things like airplanes or drones pass through it or it becomes contaminated by things we can see or smell.

It is what most closely ties us together as people. We actively absorb everything we come into contact with in our immediate environment into our bodies by inhaling it, including the pure, fresh air that is typically polluted with a variety of pollutants. Everything that crosses it has the potential to harm, wound, and alter our bodies. However, the contrary is also true: humans directly affect airspace, which serves as a transit area for substances, movements, people, and objects. Anything we release into the environment can have a negative impact on it. In other words, airspace and people are mutually dependent; we share what we produce, move, and distribute.

However, most of the time, people’s interactions with the air are unintentional or passive. However, ever since the Covid-19 pandemic, when aerosols began to influence our daily interactions, ever since the war in Ukraine has sparked vociferous calls to close its airspace, ever since the fear of poison gas or nuclear weapons being used has returned, our perception of airspace and its significance has grown even more acute. Because it not only distributes viruses but also dust, cigarette smoke, fumes, gases, and bombs.

All of this makes one very specific aspect of airspace very clear: it is a fluid space that is ultimately uncontrollable, it can expand in a way that cannot be seen by the human eye, it lacks any distinct boundaries or contours, it can be crossed at high speed, and it almost completely surrounds every single person. And because of this, it is both extremely deadly and extremely fragile. Human vision and judgment depend critically on visibility, and we require boundaries to keep ourselves safe. Based on a delicate equilibrium between permeability and impermeability, the human organism as a whole. To put it another way, we frequently only become aware of anything traveling through our airspace when our body reacts, and in other situations, we do not even know what it is until it has already gained admission. It might be the carbon dioxide we breathe, the tear gas employed by security personnel, or a virus-laced mist. More than many realize, believe, or even fear, there is a lot going on in the air.

Homosphere examines this pervasive but unseen sphere, viewing it as a place for the mysterious or unexpected, for the frequently covert assaults on not only the human body but also on people, society, and nature. As such, it is a potential danger zone for the earth system.

Artists: James Bridle, Julian Charrière, Don’t Follow the Wind, Forensic Architecture, Hemauer/Keller, Almut Linde, Cristina Lucas, Rabih Mroué, Carsten Nicolai, Walid Raad, Oliver Ressler, Tomás Saraceno, Susan Schuppli, Tétshim & Frank Mukunday

Curated by Stefanie Böttcher.

Kunsthalle Mainz

Am Zollhafen 3-5

55118 Mainz

Germany

Hours: Tuesday–Friday 10am–6pm,

Wednesday 10am–9pm,

Saturday–Sunday 11am–6pm

T +49 6131 126936

F +49 6131 126937

[email protected]

![[1] View of Indigo Waves & Other Stories, Zeitz MOCAA, Cape Town, 2022. From left: Luvuyo Equiano Nyawose, Thania Petersen, Malala Andrialavidrazana. [2] Joël Andrianomearisoa, The Five Continents of All Our Desires, 2022. Black silk paper, metal, rope. Dimensions variable. Commissioned by Zeitz MOCAA. Photo: Storm Janse van Rensburg.](https://dailyart.news/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/ZM_new-527x703.gif)

![[1] Kunstverein Toronto announcement. [2] G.B. Jones monograph cover image.](https://dailyart.news/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/kunstverein_toronto-527x703.gif)