May 26–July 1, 2022

How could we define the work of Julieta Aranda? I will start by inventing a name for her bold methods: superposed epoch analysis. What does superposition refer to here? Superposition names the way time works. Time is an active substance, a true artist and agent, able to escape the linear commonsensicality we, humans, project on it. In her hands, it becomes transparent how, through time, the transformation of life’s quotidian actions into political messages takes place. It is because we can only see time in a certain way that we aspire to frame an entire social reality and name it “history”. The domination of time’s narrative has allowed Western cultures to aspire to the domination of people, territories, imaginations, ways of narrating and dreaming that contradict that brutal take on time-realism from the part of Western science, technology, and philosophy. That’s why, again and again, Julieta Aranda’s work gains its dramaturgy from investing in what could be called time-naturalism, an approach that unveils the diversity and non-binaries of time.

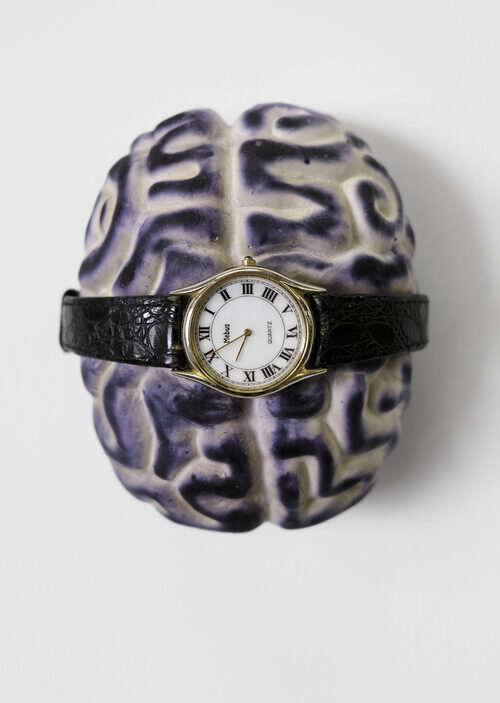

In this particular exhibition for Prometeo gallery in Milan, Aranda departs from and entangles her work with the work of Elizabeth Povinelli, a thinker and a friend of hers, anthropologist and artist supporting and voicing an anthropology of the otherwise, and Povinelli’s colleagues in the Karrabing axiom Collective. Julieta and Elizabeth engage in a study of time’s infatuation with creating an image of its own indexicality—starting with Aranda’s camera obscura sand-timers that flow upwards, like Earth itself seeing as a watch!

Povinelli explores the sedimentations, compressions and incomensurabilities of memories, bodies, referentiality as social worlds moved and shoved into the infrastructures of colonial and racial time. With a selection of original drawings and new compositions from her graphic essay, The Inheritance (Duke, 2021), and a haunting film remix of the same with her collaborator, Thomas Bartlett, Povinelli tracks the deformations of meaning and stories of her Trentino grandparents decompose as they move into the racial and colonial spaces and of the US where liberal progressive time turns into debris fields of shattered incommensurate embodiments and layered compressed sound tracks.

In The Family and the Zombie (Karrabing Film Collective) follows a group of future ancestors living within the remains of the current ecological crisis. Alternating between contemporary time in which Karrabing members struggle to maintain their physical, ethical and ceremonial connections to their remote ancestral lands and a future populated by ancestral beings living in the aftermath of toxic capitalism and white zombies, The Family and the Zombie rejects colonial clockwork in which the past is buried on the relentless domination of the future. It asks viewers to reflect on the practices of the present as the material debris on which multiple ancestral futures will be walked.

Yes, humans are as bold as drawing lines on Earth that mark time zones imposing a rhythm, and an Imperialism of days and nights and mornings through a system called “standard time zones”. Oh! Curious and rejectful of this preposterous imperative, Aranda has traveled to the very limits of this system to see it collapsing in Kiribati. Kiribati is a country in Oceania that “observes” three time zones. Colonial imposed time runs under a system called UTC (Coordinated Universal Time), which, roughly speaking, corresponds to time measured in London. I never understood it quite but it roughly says that time far away from this center can or can’t relate anymore to life in London. Like in Kiribati. If you travel 180 degrees of longitude from London in either of the two possible directions, you will end up in the same spot on the other side of the globe. This means that the UTC+12 and UTC–12 time zones should theoretically cover the same area, but they are 24 hours apart. This is why this time zone is split into two “sub-zones” of equal width (fully applying only in international waters), one being 12 hours ahead of London and the other being 12 hours behind. And yet, time-surrealism starts when the system does not work and few islands in the Pacific Ocean use the UTC+13 time zone (Tonga, Samoa, Tokelau) and even the UTC+14 time zone instead of the “usual” UTC–11 and UTC–10.

The experience of the collapse of human imperial time at its very terrestrial border, has been the subject of many of Julieta Aranda’s works, starting with You had no ninth of May! in 2009, and continuing through today with the film and photograms If you tell the story well, it will not have been a comedy, and her series of images and objects “Another end of the world is possible”, which gives name to this exhibition. This continuous exercise of detailing a case that particularly embodies power and its absurdities, together with the creation of pieces—knots—made from the remnants of ghost nets that have been spat out as flotsam by the sea, and that the artist has collected over the past decade, present dynamic and simple ways of moving away from this gritty realism. For her knot pieces, the series “The knot is not the rope”, the knots and broken pieces of rope are seen by Aranda as calligraphic propositions, presented as “written” articulations of their own failure, in a language that is not quite readable, perhaps because of our own limitations as readers, or because of the limitations of language itself.

Yet another way in which Aranda looks at time is through her interest in the intergenerational cycles of life. Images of bones, processes of decomposition and skeletal remains are fundamental in her practice, as a way to address both notions of infrastructure, and the technologies of life supporting other ideas of time, other -future- lives. Bones serve as a fertile platform, introducing matter after the more formal and conceptual languages of photography and film. Objects argue in their own and subtle way with time reminding us of the multiple orthodoxies that biology –our own time determinations—but also space impose on us.

The exhibition—through the work and voice and presence of Elizabeth Povinelli—uses extended duration as a method to keep us in the trouble—to quote Donna Haraway. The works made the minds wander as if it was performing camera movements and co-creating with us, with our presences and imaginations, an overly communal and almost choreographic collective composition able to produce counter-narratives, otherwise-dreams of those from the Modern time machines. We become then a new generation. We trespass a “line” and something long submerged reappears: the millions of vernacular and indigenous cultures of duration and life.

Prometeo Gallery

Via G. Ventura 6

Milan

Italy

T +39 02 8353 8236

info@prometeogallery.com